Renewable energy sourcing is often the key starting point.

Reduce, source, and offset

The Net Zero Pathway presented in our previous article has three actions working in parallel:

Reduce your demand, source green, offset what is left. In other words, buying green power and planting trees are not enough, and net zero first calls for eliminating the waste of clean energy, a precious resource. We also know that sourcing and offsetting will be implemented first, to deliver carbon neutrality. This is because they can take a few months while full delivery of efficiencies takes years.

In this article, we explore the growing number of opportunities to reduce your energy’s carbon footprint, highlighting the choices and cost-benefit-risk trade-offs.

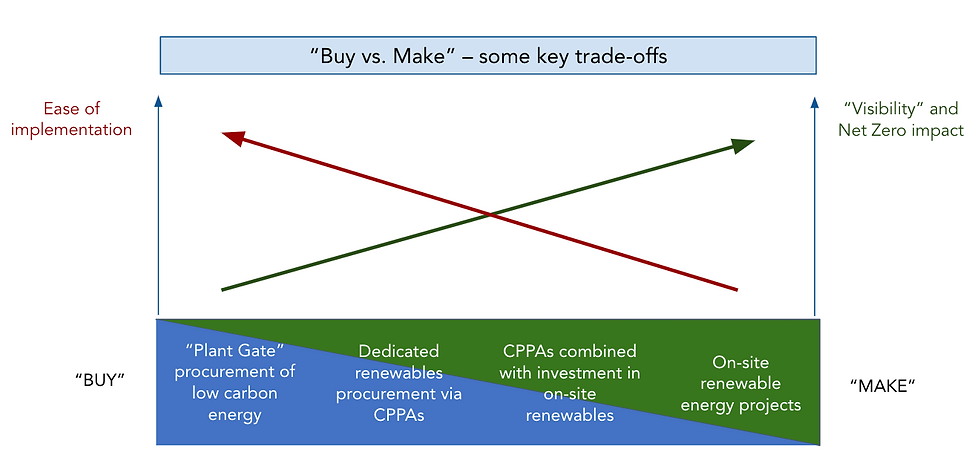

Net Zero can take many businesses into new and unfamiliar territory. Managing energy risk and project delivery effectively will be key to success, and there is an important choice between Buy and Make when it comes to cutting carbon intensity.

“Buy vs. Make” – choices and trade-offs

Turning now to the question of energy sourcing, businesses will typically have to choose among a range of different approaches – from ‘simple’ procurement of certificated renewable energy supplies from the grid right through to investment in their own on-site renewables projects. Moving away from ‘vanilla’ procurement is likely to be much more effective in demonstrating visible progress towards Net Zero goals, but it also brings with it new risks and challenges with which many businesses – especially those in the early stages of their Net Zero journey – may not be familiar.

A simplified view of possible approaches and the trade-offs involved is shown below, highlighting the continuum as companies approach the greener options.

Arm’s-length procurement of renewable energy

There is currently a sharp practical distinction between renewable electricity and renewable heat. Renewables now account for almost half of total UK power generation and this is supplemented by renewable imports. Offers of ‘green’ electricity supply are now more-or-less standard, with little or no price premium. However, that is also the drawback; businesses committed to Net Zero goals will often find it hard to convince external stakeholders that their ‘green’ electricity purchases are actually making a difference – this is the well-known challenge of ‘additionality’.

As for procuring renewable heat, the challenge is currently a different one. There is still far too little ‘green gas’ (e.g. bio-methane) in the system to satisfy businesses’ Net Zero aspirations – and large-scale supplies of hydrogen remain something for the future. Hence the continued need for carbon offsets, at least for the time being. Certificated renewable electricity and carbon offsets are rarely the targeted end-goal – but in many cases they will necessarily be part of a low carbon energy mix for some time to come.

Different technology choices will complete the energy picture based on sector specificities. Some businesses have already been buying bio-methane and investing in new equipment – especially in areas such as heavy trucking where this is the most viable low carbon alternative. Recent UK examples include Ocado and the John Lewis group. Bio-methane trucks, which are supported by the UK’s Renewable Transport Fuel Obligation, can deliver an 80% CO2 saving vs. a conventional diesel alternative.

All the Talk: Corporate Power Purchase Agreements

Corporate Power Purchase Agreements (CPPAs) are bespoke, direct supply agreements between business buyers of renewable electricity and renewable generators, sometimes from a single wind or solar farm and sometimes from a portfolio of such projects. Driven by the falling cost of renewables and increased business ambition to target Net Zero, the capacity contracted in this way has increased dramatically in recent years, to reach almost 20 GW of new CPPAs signed in 2019.

Google alone signed 2.7 GW of CPPAs globally in 2019, whilst Facebook, Amazon and Microsoft concluded a further 2.8 GW of contracts between them. The cumulative EMEA total of around 8 GW includes some 2 GW of announced UK CPPAs. To illustrate the move from arm’s-length procurement to CPPAs in the UK, the City of London Corporation recently concluded a high-profile 15-year contract for 49 MW of solar capacity located in Dorset.

In a very different sector, Northumbrian Water obtains around one-third of its electricity requirements via a 10-year CPPA with Ørsted, based on offshore wind.

Especially for those organisations contemplating them for the first time, CPPAs are complex contracts relative to procuring ‘plant gate’ electricity supplies. Pricing, credit, performance obligations and incentives are some of the critical contract provisions. One fundamental issue with CPPAs is the major profile mis-match between most renewables production and business offtakes. For this reason, many businesses and counter-parties turn to ‘sleeved’ CPPAs in which an energy trading intermediary manages that mis-match via wholesale spot market trading.

Typically, a CPPA for intermittent renewables will be priced below baseload power, to which is added the cost of a ‘sleeving’ arrangement.

Such long-term CPPAs can create significant financial and thus credit exposures for the contracting parties, which are currently difficult or impossible to cover via hedging. Businesses embarking on this approach will therefore need to ensure that their counter party arrangements are robust.

Equally important, if not more so, is a clear low carbon energy sourcing strategy within which CPPAs are to be contracted, including the following:

Competitive positioning, both within a given business sector and vis-a-vis the investment community. For example, electro-intensive data centres which are not yet exploring CPPAs are likely to be out of step with the global market leaders.

How much business demand to procure via CPPAs and how to phase CPPA procurement over time, given falling renewables costs, unpredictable future electricity prices and demand uncertainty.

Business appetite for price risk, given that CPPA prices may get out of line with the wider electricity market over 10-15 years.

How best to leverage a strong credit rating - a great commercial advantage - or manage procurement with a rating which is at risk of falling below investment grade. The importance of credit considerations can often be under-estimated by businesses which are new to longer-term energy contracting.

The interaction between CPPAs and other electricity sourcing arrangements, including shorter-term procurement and on-site renewables.

Hybrid: CPPAs plus investment in off-site renewables

This is an option commonly adopted in energy projects across many countries. As a refinement of the CPPA strategy set out above, a business could consider making a direct and normally non-operational investment (alongside others) in the renewables project from which electricity is sourced. There are some principal advantages and drawbacks of this approach that should be considered.

On-site renewables projects

Another approach to be considered as part of a low carbon energy mix is direct investment in on-site renewables projects. These are often in areas such as solar PV and bio-methane, with the former typically much more straightforward technically than the latter. Businesses which go down this route may often turn to experienced third parties for project development and O&M services. Project financing is also an option, depending on the business balance sheet and access to capital.

There are many advantages of developing clean energy projects on-site, but with various issues/risks to be considered carefully before launching into this.

There are numerous UK examples of business which have gone down this route, from which the following is a small illustrative sample from diverse sectors:

By 2019, Associated British Ports had installed renewable energy production at 16 of its 21 UK ports, delivering over 12% of its total electricity requirements. This included 15 MW of solar and a further 5 MW of wind capacity.

Thames Water contracted Lightsource BP to develop a large 6.3 MW floating solar project on its QE II reservoir, which is linked to its private network. In 2019, Thames reported that 22% of its 2018/19 electricity needs were met from solar, wind and sewage projects.

The Balanced Energy Network (BEN) at London South Bank University is a cost effective, flexible, and scalable district heating networks to deliver heating and cooling. BEN transfers warmth between buildings and extracts it via heat pumps in each building: the internet of heat. The source for heat is the London Chalk Aquifer which maintains a steady temperature of 14°C all year round.

Leading craft beer producer Brewdog is currently developing a plant to produce bio-methane from brewing waste, to be operational in 2021, and has announced a suite of other initiatives including a ‘double offset’ of its remaining CO2 emissions.

*more on offsets in the next blog

The Operational Energy-Sourcing Mix

A key challenge for many businesses committed to Net Zero will be how to integrate a variety of measures in order to deliver on sustainability goals in a cost-effective manner which does not compromise core day-to-day operations. The reasons for phased development of a mix are several:

Management ‘bandwidth’ to develop and manage a low carbon energy portfolio, alongside core business activities, whilst allowing for the opportunity of ‘learning by doing’.

The need for appropriate phasing of low carbon sourcing, outlined above.

Matching the profile of business energy demand, at acceptable cost and risk.

The detail of the overall sourcing mix are likely to vary considerably from case-to-case, depending on the sector, business energy demand pattern, financial/management ‘bandwidth’ and the stage of the Net Zero journey, as well as many other individual business circumstances.

We show one example of a typical business electricity ‘load curve’ (by half hour, from 23:00 one day to 23:00 the next), together with a mix of sourcing arrangements, viz:

An on-site solar facility, typically producing most in the middle of the day.

A CPPA for off-site wind, with variable and intermittent output not matching the load profile of the business.

Arm’s length procurement contracts, which for simplicity we represent as a mixture of ‘baseload’ and ‘peak’ (though in practice they are likely to be much more flexible).

A ‘sleeving’ (or ‘balancing’) service provided by an energy trader to handle half-hourly mis-matches between procurement and load. In practice, some of this flexibility could also be provided via on-site battery storage.

This chart focuses on electricity, but real-world business energy demands are more complex – including process energy use, space heating and transport, among others. A range of other clean technologies and initiatives are likely to be brought into play. For example, Turquoise International are fund managers for the Low Carbon Innovation Fund, with a focus on supporting SMEs and helping to arrange finance for clean tech businesses seeking to bring new low carbon/clean tech technologies to the market.

Managing Director Ali Naini recognises the strong spur which Net Zero is giving to investment in a wide range of clean technologies:

“Net Zero clarifies which sectors need to improve - all of them - and the ultimate destination, which is full rather than partial reduction of man-made greenhouse gas emissions. Although we don’t have all the technologies and business models required to get there yet, Net Zero and the success of earlier clean technologies such as wind and solar power gives Climate Tech investors a framework to invest in and to encourage other investors to join us.”

There are already multiple examples of businesses ‘packaging’ low carbon energy sourcing with other complementary investments en route to Net Zero - for example, in the retail, transport and distribution sectors. These include:

The Ocado and John Lewis/Waitrose examples of investing in new HGVs which use bio-methane fuel, in place of diesel.

Tesco, which is investing in both solar projects and electric delivery vehicles.

Bus fleet operators, who are increasingly ‘packaging’ investment in electric buses with solar electricity, battery storage and enhanced grid connections.

Key points on renewable energy sourcing

Effective and proactive management of energy use and sourcing will be a key element of delivering any Net Zero business commitment. The good news is that there are proven pathways to delivery and more of them are becoming viable as the cost of low carbon energy continues to fall.

Businesses embarking on the early stage of this journey will first need a clear, coherent sourcing strategy – both to fit together the pieces of the sourcing ‘jigsaw’ and to manage risks and issues along the way.

That sourcing strategy is not a ‘one and done’ event – the future is uncertain, circumstances are bound to change and businesses will need the AGILE prioritisation capabilities outlined on our previous blog.

In our final Net Zero blog, we will reflect on the depth of transformation required in both organisations and markets to deliver net zero collectively, and share the hurdles faced by those already knee deep in the journey- if you have a net zero story to share, please get in touch!

About us:

Ampersand Partners is a management consultancy, whose Energy Transition and Sustainability practice helps energy companies navigate their fast changing market environment and non-energy clients deliver their net zero ambitions.

Net Zero Enthusiasts (NZE) is a small-group of seasoned independent energy sector professionals who between them have over 100 years of experience in the industry, advisory firms and providers of finance. Based on long-standing connections, complementary backgrounds and a common commitment to decarbonisation, the NZE have come together to support the UK’s low carbon transition.

Sources:

Comments